By Radio Yapti Tasba Bila Baikra

The day passes with apparent normality. A group of women gathers in the community center and prepares food for a community event. Just a few meters away is the school, where some girls and boys attend classes. It is harvest season for rice; community members are drying, cleaning, and husking the grain. However, their faces cannot hide the uncertainty that weighs on them. In the community of Wiwinak, located on the banks of the Coco River, there is fear—just a few kilometers away are the “third parties,” land-invading settlers who threaten to dispossess them of their plots.

In the Miskitu community of Sagnilaya, on the Wawa River, about 60 kilometers from Puerto Cabezas, the reality is the same. The Indigenous community also fears disappearing, as the settlers do not cease their invasion plans and threats. In Sagnilaya, Félix Lavonte Centeno feels nostalgic for the life they had before the settlers arrived. Now the forest, the wild animals, and many fish are gradually disappearing.

In Sagnilaya, the community members harvest crops on the other side of the Wawa River, so they must cross frequently. However, this has not been possible for some time now, because armed settlers roam the area and have opened trails (cleared paths) from the riverbank. “They have made trails along the Wawa River and have said that no Miskitu person can cross to the other side of the river to work, to clear rice, beans, or cassava, or anything because it all belongs to them... they have been in these lands for some time now, and if you go into that mountain, you’ll see they’ve already built a small settlement,” says a community member.

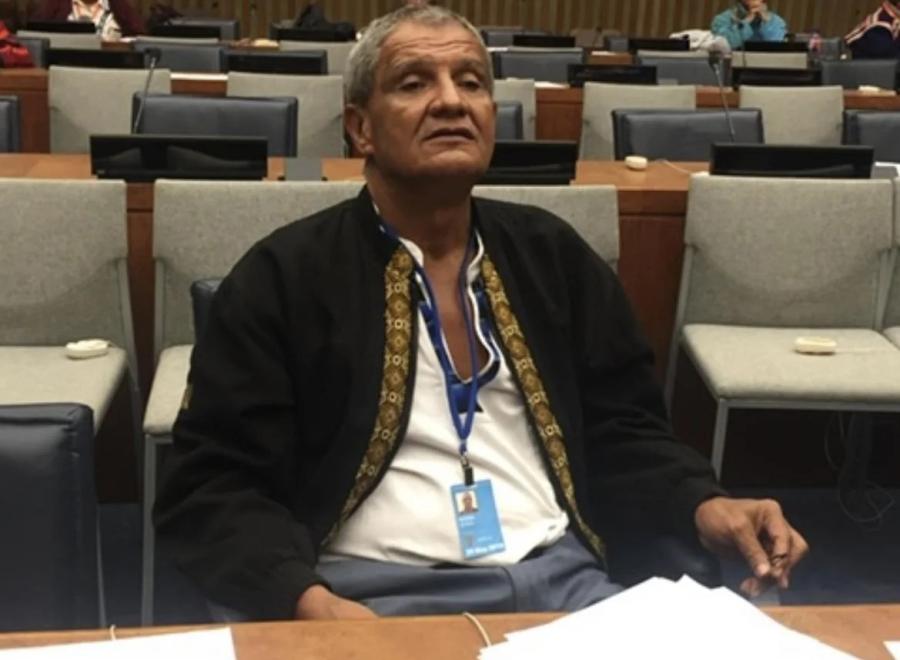

Apolinar Teylor is a native of this community and refuses to leave the land he has worked on. He has been a victim of settler aggression; in 2020, his shack and those of four other community members were burned down. Despite this situation, he continues to fight for the land-titling (sanitation) process to be fulfilled for the lands they cultivate.

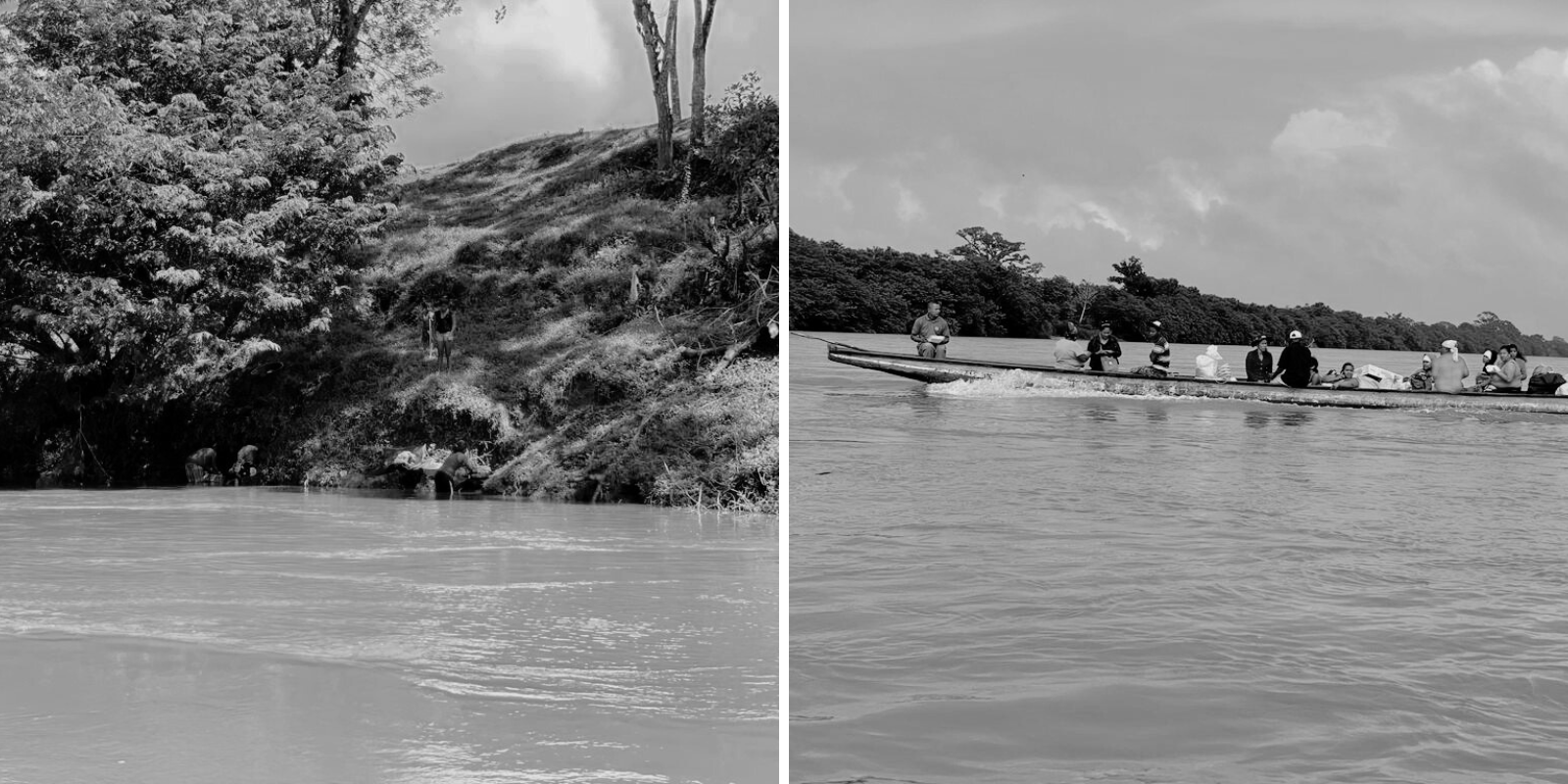

Wawa River in the community of Sagnilaya – Coco River, is one of the sources of livelihood for the Miskitu and Mayangna peoples.

The resistance of Indigenous communities is a constant challenge, and news of communities being attacked circulates throughout the region. In 2020, the community of Alal was set on fire by armed men, and six forest rangers were killed during the attack. A year later, on August 23, 2021, another tragedy shocked the country: invading settlers massacred nine Miskitu and Mayangna Indigenous people who were engaged in artisanal mining on Kiwakumbaih Hill, located about 10 kilometers from the Musawás community in the Mayangna Sauni As Indigenous territory.

In both cases, community members identified the responsible party as a gang led by Isabel Meneses Padilla, known by the nickname “Chabelo.” However, the Ortega regime’s justice system unjustly sentenced four Mayangna individuals to life imprisonment for the Kiwakumbaih killings. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) granted provisional measures for the imprisoned individuals and requested that the State of Nicaragua “immediately proceed with their release and take the necessary measures to effectively protect their lives, personal integrity, health, and freedom.”

A new massacre occurred on March 11, 2022, this time in the community of Wilú, in the Mayangna Sauni As Indigenous territory. A group of armed settlers violently stormed the area, killing five community members, injuring two, and burning down 16 homes and a church.

“We are facing an ethnocide of communities that is physical, cultural, and geographical,” said a Miskitu leader.

The boat or canoe is the main mode of transportation for Indigenous communities settled along the Coco River – Women from the community of Klisnak wash clothes in the Waspuk River.

Forced displacement and the ongoing loss of their lands

After the attack on the community of Wilú, the population (about 70 families) was forced to flee to Musawás and nearby communities to protect their lives. When migration is not forced, it is a routine part of life in these communities—but when it is the result of violence, it disrupts their entire way of life. “The main cause is fear, the need to protect life, and the search for food. If they don’t move, they either get killed or die of hunger,” warned a community leader.

The communities most affected by forced displacement include Francia Sirpi, Santa Clara, La Esperanza, Río Wawa, and Wisconsi, all located in the Wangki Twi Tasba Raya territory. Since 2015, a continuous process of invasion and violence has been unfolding, driven by non-Indigenous people seeking resources for illegal mining or cattle ranching.

Another area heavily affected by forced displacement is the Mayangna Sauni As Territory, particularly the communities of Musawás, Wilú, Alal, and Betlehem. Some communities in the Tuahka Indigenous Territory, located in the municipalities of Rosita and Bonanza—where mining activity is intense—are also affected. The Mayangna community of Wasakin is among the most impacted by displacement.

The dynamics of forced displacement are experienced in different ways. In some cases, entire families relocate to nearby communities that are not facing as many conflicts. In those host communities, local authorities offer them shelter and a piece of land to work on.

Others have moved to larger towns and cities, such as Waspam and Puerto Cabezas. Sometimes, only the head of the household migrates in search of work, sending money or provisions to support the family who stays behind in the community—though they can no longer access their land, which is their main source of livelihood. In other cases, the entire family relocates to the municipal centers.

According to the community leader, in some instances, those arriving in neighboring communities are given a small plot of land to work on, where they can plant seasonally. For those who end up in the city of Bilwi, the situation becomes more difficult. “Men sometimes have no choice but to go out to sea and work as divers; it’s the only job they can find. They end up disabled because they lack the training, but they do it out of necessity,” he explains.

As for women and youth, many seek work as domestic workers. Others sell lemons, oranges, pijibay, and stuffed pastries (enchiladas) in strategic areas of the city like gas stations, banks, and parks. “There was a case where a young girl went with her mother to help with domestic work, and the employer’s son tried to abuse her. When the mother spoke up, both were thrown out without any pay,” the community leader recounts.

The activist adds that Indigenous populations are unfamiliar with the concept of city life and lack steady jobs to help them survive. “Sadly, some women have been forced into prostitution, leading to sexual abuse and early pregnancies. Without a home, they live in huts on the outskirts of the city, facing all the hardships and needs you can imagine,” he says.

“I cried when they took my land.”

It’s been nine years since “El Pastor” arrived in Puerto Cabezas. He used to live in La Esperanza Río Wawa, a community he remembers as green, with about 60 houses and 700 people, but which is now suffering from migration caused by violence and land invasion. “Some of us are in Puerto Cabezas because we fled, out of fear. I was one of the last who still had a lot of land. I went to my farm, and I couldn’t get in. A settler was there. I talked to him, and he told me that those who sold him the land gave him signatures and everything. They came from the Pacific side. He said the government supports them and gives them AKs,” he recounts.

His eleven children and fifteen grandchildren now live in a neighborhood in this coastal city, but they long for the life that was taken from them. “When I lived in La Esperanza, I used to grow bananas, cassava, taro, rice, beans—I produced a lot. My house was full of all kinds of ripe bananas, and we had plenty to eat. But now we’ve been left with nothing.”

El Pastor explains that when they arrived in the city, a man gave them a place to stay, and a young woman offered them a small piece of land to plant cassava. “We’re not doing well. The soil here isn’t good, so we can’t work it. We used to grow cassava on that small piece of land, but now we can’t because it floods when it rains.”

The greatest difficulty for this family is finding a job. “When I go to look for work, they tell me, ‘You’re too old, you can’t work anymore,’ but when I was in La Esperanza, I could work because I had my land,” he says.

“Sometimes I suffer for not taking wabul,” says “El Pastor” during the conversation, but he affirms that he doesn’t lose hope of returning to his farm.

Structural violence and an imposed development model

In Nicaragua, the stage of land tenure regularization for Indigenous territories, as established by Law No. 445, the Law of the Regime of Communal Property of Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Communities of the Autonomous Regions of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua and the Rivers Bocay, Coco, and Indio and Maíz, has not been fulfilled. Neither has the Statute of Autonomy for the Regions of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua (Law No. 28), in effect since 1987, been respected.

On the contrary, the Ortega Murillo regime has promoted development plans and models that undermine the livelihoods of Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. While they haven’t been the only ones, the community leader argues that every government has attempted to impose an economic model that is not Indigenous, primarily focused on the indiscriminate use of natural resources, through the establishment of mining, which encourages the invasion of forests and lands where Indigenous peoples live.

House of community members in the Klisnak and Wiwinak communities along the Coco River.

The indiscriminate exploitation of resources conducted without the consent of the communities has also undermined their forms of governance. “This has been evident in many conflicts of interest where many government officials have businesses in the territory,” explains the activist.

Behind these conflicts are those who hold economic power, political power, and the power to wield arms. “What they do is take control of the productive areas of the communities, turning them into pastures. Then comes the conflict of murders, kidnappings, and, as a result, it forces the community members who are left without land to migrate,” the Indigenous leader explained. He added that some migrate to the cities of Waspam or Puerto Cabezas, others cross into Honduras, and some opt to go to Costa Rica and Panama. Since last year, migration has extended to the United States.

Another model being imposed in Indigenous communities is the agrarian model: “planting excessively, clearing land excessively, and then having cattle ranches to later export the meat.” In the activist’s view, this fuels the invasion.

Apolinar Taylor reaffirms what has been stated. “They make pastures, bring in cattle, mules, raise pigs and chickens, they do whatever they want. They don’t work on a small scale; if you were to see, even a helicopter could land there. We have food problems. Here, people go to the plains, and you’ll see how destroyed it is. There are no pines anymore, because since we don’t have anywhere to work for food, people decided to burn charcoal, which is sold in the market, and with that, we buy a handful of rice,” he recounts.

This is compounded by the effects of climate change. In November 2020, the Northern Caribbean region was impacted by hurricanes Eta and Iota, which were Category Four and Five, respectively. These hurricanes caused the loss of livelihoods for various communities, mainly coastal ones.

“The community of Haulover was almost completely destroyed, and many people never returned to their community because they no longer had the means or access to sustain community life, so they stayed in Puerto Cabezas or migrated to Costa Rica, Panama, or the United States. Here, the migration phenomenon is different; it’s mostly young people who are leaving to support their families,” explains the activist.

The community leader mentions that it is the community members who are trying to rebuild their homes, and the regime has only supported them by providing zinc sheets. “The state has not created the necessary conditions for the communities to be resilient to all the negative impacts of a hurricane,” he asserted.

In the face of such an adverse context, the resistance of many community members remains in all actions defending their rights, promoting their own ways of life, and sustainable development.

Indigenous communities continue to speak out. For the community leader, “the only option is for the State of Nicaragua to have the will to respect the rights of Indigenous communities and take concrete actions to stop the growing process of invasion or colonization.”

However, he warns that “for now, we don’t see that light, what we see is more darkness because, for state policy, the invaders are resources that favor their interests.” Despite the circumstances, the communities do not abandon hope for change. “We are dreaming that all of this will end someday,” concludes the activist.

In 2022, Radio Yapti Tasba Bila Baikra was supported by the Indigenous Community Media Fund, which provides opportunities for international Indigenous radio stations to strengthen their infrastructure and broadcasting systems, creating training opportunities in journalism, broadcasting, audio editing, technical skills, and more for radio journalists from Indigenous communities around the world. In 2024, the Indigenous Community Media Fund supported various communities with 57 grants totaling $450,000 to Indigenous community media in 20 countries, supporting 87 Indigenous Peoples.