By Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey)

In rural Alaska, where six months of darkness shape daily life and traditional stories lean toward horror, Indigenous filmmakers are reclaiming narrative power.

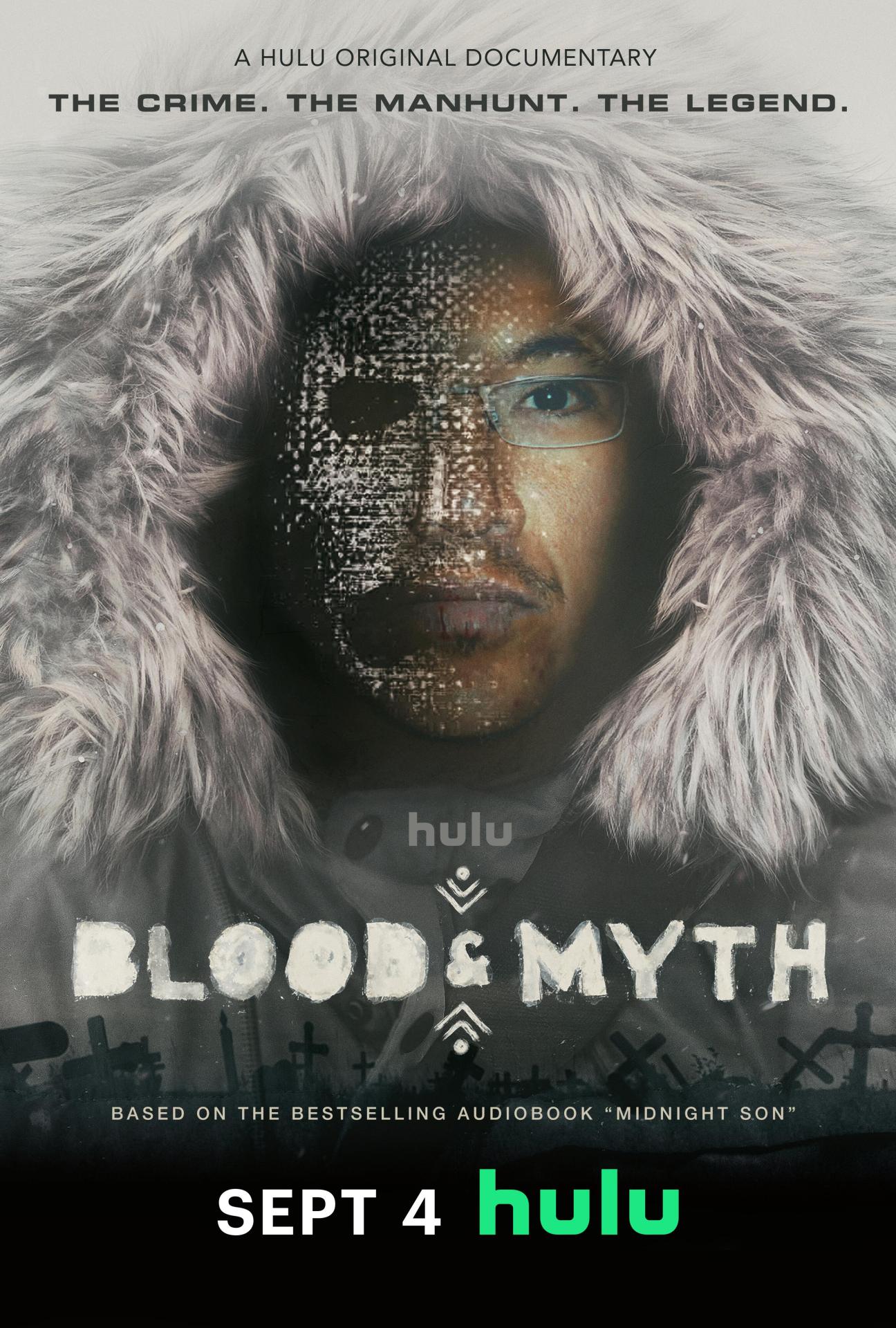

Hulu's new series “Blood & Myth” breaks new ground not just as true crime, but as an act of Indigenous reckoning. Executive Producer James Dommek Jr. (Iñupiaq) and Director and Executive Producer Kahlil Hudson (Tlingit) bring us the haunting story of actor Teddy Kyle Smith, whose descent into violence is intertwined with spiritual beings known as Inukun (“little people” in Iñupiat) and the blurred lines between myth and reality.

In this interview, Cultural Survival Quarterly Contributing Arts Editor Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey descent) speaks with Dommek and Hudson about their creative process, their perspectives on the cultural reality of myth, the significance of Inukun stories, how “Midnight Sun” evolved into “Blood & Myth,” and much more.

Phoebe Farris: During the Indigenous Media Conference, the word paranormal was used frequently in reference to “Blood & Myth.” Is there a word in the Inuit language that is similar to paranormal?

James Dommek Jr.: The closest words I know convey fear, one for physical danger, another for fear of something unseen. The culture in itself, before contact, revolved around a lot of spirits and a lot of reincarnation. We had a really animalistic animism-type religious set. We did believe in these paranormal; we did believe in things not seen. It was definitely part of the culture. It's because it's such a hard place to live, we do really enjoy very scary stories—a lot of traditional stories lean towards horror and towards the darkness of it all. Alaska can be very dark in the winter; the stories reflect that.

PF: You’ve mentioned the book “The Eskimo Storyteller,” which your great-grandfather helped write. Tell us about its significance to the film and its impact on you and your family.

JD: The book was written by an anthropologist who went to the little village of Notak, Alaska, in the 1960s. My great-grandfather, Palagan, did not speak English. He was born before the missionaries came. He was raised in the old ways. The English name assigned to him was Paul Monroe. This anthropologist by the name of Edwin Hall went to the village of Notak in the '60s and hired a translator. He wanted to know all the stories. He got the two storytellers in the village and had them tell their stories. They told the stories in our language, in the Yupak language, and the translator would tell the anthropologist in his broken English, the translation, and the anthropologist wrote them down word for word. The book is written in almost pidgin English, as they call it in Hawaii. My great-grandfather was a very old man when he told the stories. He died shortly thereafter.

James Dommek Jr.. Photo courtesy of Hulu.

James Dommek Jr.. Photo courtesy of Hulu.

PF: This is before you were born or were you a child during this time?

JD: No, I was born in 1981. This was done in the '60s. I never met him, but I grew up reading the book and reading the stories and realizing that I believe that he understood the cultural significance and importance of documenting these stories in this new way of storytelling, which is in books. The book has always been my North Star as far as my storytelling, my base for it, what I understand. Through “Midnight Sun” and through “Blood and Myth,” it was always a reference point. My family and I are very aware that he was a storyteller, that our family did this. I'm happy to continue that on with new mediums.

PF: Was your great-grandfather compensated in any way for these services?

JD: It was understood that the proceeds from the book would go to a scholarship fund for the kids in the Village. Edwin Hall was with a religious organization of some sort, but it says in the prologue of the book that all the proceeds from that book went on to fund some scholarship. I'm not quite sure what he was compensated with or for.

PF: Kahlil, what is your perspective as the director and executive producer and someone who's a part of the culture?

Kahlil Hudson: Regarding your first question, if there's a word for paranormal, the separation between myth and reality is very thin up North, and it almost doesn't exist. So what we consider as someone... I'm Tlingit, so I'm from the Southern part of Alaska. I'm a different tribe than James, but we have some similar beliefs. We don't have Inukuns, but we have Kushtakah [mythical shape-shifting creatures], which have some similarities. When you're talking about the paranormal and this idea of paranormal, we don't consider Kushtakah paranormal. In the Veltas, they don't consider Inukuns paranormal. They're alive, they are understood to be real. There is power, shamanic power that exists in the world. You have to take a different mindset when thinking about these things. It's because these things are not paranormal. They're very real. That's something that was reaffirmed for me in making this story; these beliefs are like asking a Christian if Jesus was real.

Teddy Kyle Smith and James Dommek Jr.. Photo coutresy of Hulu.

PF: You mentioned that Teddy Smith's story could be a cautionary tale or a changemaker. How has this story kept you on the right path?

JD: With the American dream comes a lot of freedom, and you have the freedom to make it, or you can fall victim to maybe your vices, the distractions, and the pitfalls in life. If you want to be a movie star or a rock star, there are these pits, these traps, and these pitfalls along the way. Since the advent of the movie industry and the music industry, people with talent who want to make it have tried to get themselves out of poverty or their family out of poverty. They try to make it, they go for it, and there are just too many distractions, too many vices, and they fall victim to them instead of facing their demons. Underneath it all, Teddy's cautionary tale was behind the layers.

PF: Please briefly discuss the audiobook, “Midnight Sun,” and its influence on making the documentary, “Blood and Myth”?

JD: “Midnight Sun” came first. I always knew the story would be good, and I always thought it would make a good movie. Because I had been in the movie, worked in film production and crews up here in Alaska, I knew it takes an army to make a movie. A podcast or an audiobook just takes a couple of people. So I thought, ‘I'll have to do that first.’ So I made the audiobook, put it out in 2019 with my friends Isaac Kestenbaum and Josie Holtzman from the East Coast, and it was just my first foray into telling stories, and “Blood and Myth,” the documentary, is a continuation of “Midnight Sun.” It's just not a cut-and-paste copy of the audiobook. It's two completely different things, two different perspectives of the same story. There are things in the audiobook that didn't make the doc, and there are things in the doc that did not make the audiobook. They're all about the same story and the same person.

Kahlil Hudson. Photo coutresy of Kahlil Hudson.

PF: Kahlil, do you want to add anything about the book and its influence on the film?

KH: The audiobook had been out for a year or two when I first heard it, and I was blown away. One of the first questions we asked was, ‘How are we going to make this documentary new?’ Because this story has been told, but James would agree, I think he never quite felt like he had... In fact, he didn't get to interview certain people because Teddy refused, just ignored his request for interviews while he was making the audiobook. There were a couple of other interviews that he couldn't do. We went after those new interviews hard, and it took quite a bit of discussion and earning people's trust to speak with us. We think of the documentary as an evolution of the audiobook. They're both very different.

PH:. During the Indigenous Media Conference, the term Inukun was mentioned. The word is ubiquitous or unknown to the rest of the world. So why did you feel it was okay to expose the name now?

JD: Well, these stories were not taboo for us. The Christian Church and the religion made talking about these stories taboo. They were never a private thing. There are some cultures up here in Alaska that are very closed off. Inuit culture spans across four different countries. We're in Siberia, we're in Alaska, we're in Canada, and we're in Greenland. But what's interesting about this Inuit origin story is that every single Inuit group from Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia has this same story of how these little people came to be and how we used to live alongside them. It's the exact same story of why they left. The reason why it's not googlable is that people aren't really interested in Native folklore. The outside world is not interested in native folklore. In Inuit culture, especially Inupat culture, out of all the American Indian groups, out of all the native groups across the United States, Alaska, and the Inuit were the last to be discovered. We were the last to be nomadic and wild, and live as our ancestors did. The government had to beg my people, the Inupiat people, to stop being nomadic. That was in the early 1950s. We were still living off the land, wearing furs, following the caribou. We're still very connected to the land up here.

We're still very connected to the stories. To us, it's not a taboo thing. It's probably the same thing for the Pacific Northwest Natives to talk about Sasquatch. Because that's a cryptid that exists in that area of the world, there are all these Tribes in that area that all have a similar story about this tall, hairy thing. This is our version of that. To me, it's more plausible than a Sasquatch. It could just be these wild people who just didn't want to have anything to do with any civilization. Alaska is a place where there's enough food, and there's enough water. It's a very hard place to live, but there are life-giving things. If you know how to do it, you can survive.

PH: In addition to co-writing, narrating, and scoring the audiobook “Midnight Sun,” you wrote another book, “Alaska's the Center of the Universe,” and played drums in several bands. How do you balance your creative pursuits while raising a family? And what aspects of your life led you to pursue careers in the arts?

JD: Those are just things that made me happy. I like playing music. It just called to me. I grew up in the late '80s and early '90s, and it was a golden age for music and film. I was able to watch it all. It was very inspired by bands, by music, and film. I wanted to be a part of it somehow. My kids and my family keep me grounded. I love to hunt. I love to fish. I love living in Alaska. There are things that I get excited to work on, and they're fun to me. I like being around the action. It's very fun making a film. It's very exciting to be around the crew.

KH: I'm not a Renaissance man like James. I only make documentary films.. But I am a cinematographer and an editor. I do wear multiple hats at times. We're lucky to have James with so many talents, just because he had his hands in everything from the score. He recorded some Inupiaq drums to incorporate into the score. That's just one of many ways in which he was absolutely integral to the production of this film.

--Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey descent) is Contributing Arts Editor for the Cultural Survival Quarterly magazine. An art critic, curator, author, and photographer, she has written extensively on Indigenous visual, literary, and performing arts for over two decades. Farris is also a Professor Emerita of Art and Design at Purdue University and has curated and contributed to exhibitions highlighting Native and global Indigenous artists. Her work bridges scholarship, creative practice, and advocacy, amplifying Indigenous voices in contemporary art and media.

Top photo: James Dommek Jr.. Photo couresy of Hulu.