By Cristina Verán

From street cyphers and Rez rap battles to cross-cultural community building on far-off continents, Christopher Mike-Bidtah (Diné)—aka Def-I—has built a career approaching his craft as a living cultural practice, shaped by place, language, and memory. His trajectory traces oft-overlooked Indigenous lineages of hip-hop in the U.S. Southwest, particularly in its Four Corners region, where participants have been repping the culture’s foundational Four Elements—MCing, DJing, Breaking, and Graffiti Art—for decades. As a new kind of culture bearer, Def-I understands his hip-hop engagement not simply as performance, but as responsibility—one that calls him to use his voice in service of both the music and the movement.

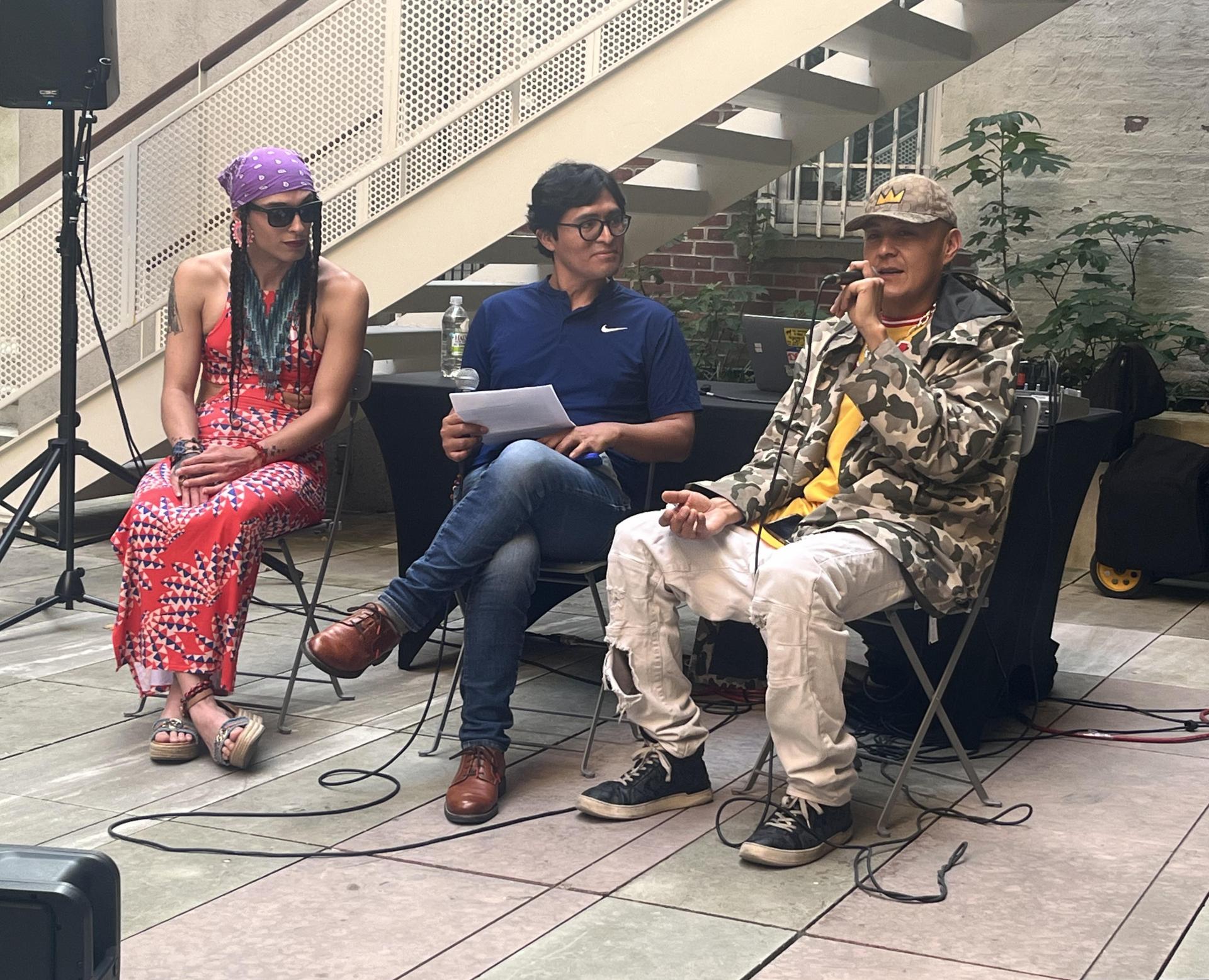

In conversation with Cristina Verán, Def-I reflects on his early influences, formative experiences, notable contributions, as well as what it means for him to be a member of both the Navajo Nation and another, much newer “tribe” that first emerged in the 1970s from The Bronx, NYC.

Cristina Verán: Tell us a bit, first, about where and the environment around which you grew up.

Def-I: I was born in Albuquerque and raised in a part of the city locals call “the war zone” because there’s a lot of poverty around. Even so, as a little kid, it felt like a great place to grow up because our neighbors and friends were this really cool mix of people. I moved to the Rez, to Shiprock (on the Navajo Nation), to start elementary school—a big change for me—and later bounced around a bit, also to Farmington, then to Gallup, before moving back to Albuquerque as a teenager.

In Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Photo by Joshua Mike-Bidtah.

CV: What are some of your foundational memories involving hip-hop, and what made the music in particular resonate for you?

D-I: Run DMC was the first group I heard on the radio and really liked. I loved how cleverly they and other rappers used words and would tell all these stories in their rhymes. I have to credit my mom for instilling this appreciation in me, actually, because she valued education and had taught me how to read and write when I was really little. I fell in love with words from then on, seeing them flow out on paper, in the rhymes of poets, and through the music of hip-hop.

I had this really cool poetry instructor in Shiprock back then, Mr. Kelly, who was originally from the Bronx! He really liked rap for its wordplay and encouraged us to do it, so we would meet up to perform our own original rhymes during poetry slams at our high school.

CV: Every local hip-hop community, beyond the culture’s New York place of origin, develops its own “genealogy” in relation to and within the movement. Who are some earlier Diné hip-hop figures we should know about?

D-I: A lot of us are really diving into this history now! I was surprised to find out that there were breakers dancing on my Rez as far back as the '80s—b-boys like Majestic Rockers, for example—who taught the next generation I’d eventually meet on my own journey. As far as MCs here, Chandler Willie was really cool, and he’d often come around to the Shiprock jams. Also, Mystic & Shade, plus my older brother Shane B. I remember this other Diné rapper, too, named Natay. In fact, one time when I was a little kid, Chandler brought him over to my house as a surprise. It was still pretty early, and I was asleep, but my parents let him go to my room. Suddenly, there’s Natay, yelling at me: “Wake up! Wake up! Wake up! It’s the first of the month!” I’ll never forget that.

As for other early Indigenous (non-Diné) hip-hop artists, the most well known here were Supaman (Apsáalooke) and, before him, Litefoot (Cherokee)—who would come out to my Rez quite a bit, bringing other Native rappers to perform, too.

CV: What—as far as the scene and the people in it—began to draw you in deeper, toward some kind of hip-hop “coming of age” moment, if you will?

D-I: Well, I looked up to this DJ named Cedro (Bert Benally)—a serious record collector who built his own sound system to throw jams on the Rez. He’d bring a bunch of artists together to perform each time: MCs and especially DJs like Cutting Bear (now known as Poetic Cee), Abel Rock, and so on. Then one day, he passed me the mic, and I rapped for the crowd! After that, I began entering MC competitions to battle other rappers, getting better in the process.

The Navajo Nation Fair out in Window Rock had, meanwhile, begun hosting b-boy and b-girl dance battles, and the Phunky Foot Rhythm Crew was organizing some great hip-hop events. Then a guy named Mike 360 started doing a bunch of dope jams in Albuquerque, even bringing out some of New York’s hip-hop Elders—I met graffiti legends Phase 2 and Coco 144 at one of these. Between say, 1998 to 2002, I went to as many of these as I could, and that led me to find other like-minded people who would eventually become some of my best friends and collaborators.

It soon became apparent to me that hip-hop wasn’t just something I got into for fun, but more like “this is who I am,” as an identity.

At New York University's Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, along with rapper Bobby Sanchez (Quechua) and Professor Renzo Aroni Sulca (Quechua). Photo by Cristina Verán.

CV: The original social experience of hip-hop was (and still remains for many) centered in collectivity, forming a new kind of “tribe”, if you will. As both a Diné person and a hip-hopper, the identity you embrace grounds you in both communities—one from birth and the other by choice. How did you start connecting with other Native hip-hop heads that, like you, also walked the two roads?

D-I: I’d heard about this all-Native hip-hop collective in the region called Foundations of Freedom, whose members were primarily Diné, Hopi, and from some of the Pueblos. They started out as mainly a dance crew, and then some DJs and graffiti writers joined, too. Their whole vibe really resonated with me, so when I heard they needed an MC, I drove to meet them in Gallup, where most lived at the time. That's how I became part of a crew—and my buddy, Wake Self [R.I.P.], was recruited, too, to rap with me at their events.

CV: At what point did you actually start recording your music?

D-I: My older brother, Laurence Shane Bidtah (aka Shane B)—already known for throwing the Rez Life Music Fest in Shiprock—was also a poet, and he said to me that he wanted us to write and record some verses together. We teamed up with a neighbor from our Rez, Gabe Dixon, to make beats for us to rhyme over.

CV: From the signature, intricate and rapid-fire battle-rap you developed through live performances to the ways in which you’ve honed your craft for more polished studio recording, how would you describe your style—and do you feel like it has changed much over time?

D-I: My style has definitely evolved. I’ve always been pretty aggressive on the microphone, but I’ve learned to control some of that energy when I'm trying to focus more on the message I want to put out there. I would describe my rhyme-flow like water, with a lot of spurts, in a kind of cursive path, versus a more jagged and straightforward lyrical take. I learned how to pause, to take a breath, letting that affect the way my words come out so the listener can have an extra few milliseconds to absorb the message—right before I go back and start rapping again fast.

With high school students in Ramah, New Mexico, during a recent tour through Gallup-McKinley County schools. Photo courtesy of Def-I.

CV: Where does Diné Bizaad, your language, figure in this—if at all?

D-I: I’ve made it part of my trademark style to include pieces of it in certain songs; for example, throwing a word like “ch’izhii” (rough) in something, to rhyme with another word, like “gólízhii” (skunk). The Diné language—which I’m not fully fluent in (despite having taken classes in it)—is not as easy to rap in as other languages can be, alas.

CV: How did you begin to meet hip-hop artists from the rest of the country? Did you travel to find them, or were they coming to your area?

D-I: It’s like this: Route 66, which cuts through this region, made Albuquerque a good stop for both mainstream and underground artists to make while on tour, while making their way to Chicago, LA, or some other place. Whenever one of my favorite artists came to perform, I’d stick around like an eager lil Rez kid and try to meet them, introducing myself and then rapping some verses to see what they thought. That’s how I connected with Evidence, from the group Dilated Peoples. He encouraged me, and I actually got to tour with him, years later!

I got to meet some of the dopest rappers that way, like Myka 9 (fka Mikah 9, of Freestyle Fellowship), Percee P, Fat Lip (of The Pharcyde), and Medusa, when they came out here—and Wake Self and I ended up opening for their shows! I'm so thankful for those times, for artists like that who gave us the opportunity and also the courage to keep going.

CV: Let’s shift to your international hip-hop experience and adventures. How did this all come about?

D-I: I met this guy, Junious Brickhouse (from The Assassins dance crew), after one of my shows. As a hip-hop artist, he loves to travel the world to meet other hip-hop heads and get to know about their communities. Eventually, he started working with Next Level, a hip-hop cultural diplomacy program that would bring U.S. artists to other countries, and he encouraged me to apply for it. I was interested to share my traditions while also learning about the traditions of other places, so I did—and was accepted for Next Level 5.0 in 2018.

CV: What are some highlights from this hip-hop ambassador experience?

D-I: When we were in Abuja, Nigeria, we collaborated with Blackbones theater company and dance collective. We did a kind of “drum exchange” while the dancers got to dance in the cypher. They’re such advanced percussionists, and I felt honored to just be in the circle with them. One of the dopest Nigerian rappers, who also has his own record label—an emcee known as M.I Abaga—came out to jam, too.

I asked audiences there if they’d ever seen or met any Native Americans before. Surprisingly, a few actually said they had, though not in a hip-hop context. They wanted to know what it's like on my Reservation, to talk about things like arts education and entrepreneurship, as well, to just share stories about each other's lives. When I went out to visit their communities, seeing their local markets and such made me feel like I wasn't so far from home. It all reminded me of being out on my Rez. I was especially impressed to see that while most Nigerians know English, they continue to speak their tribal languages, too: Ibo, Yoruba, Hausa, and others—and have their own kind of slang that mixes pieces of each together.

Performing in front of the famous Luxor Obelisk at the Palace de Concorde in Paris, France, with DJs Jo Unique and Amore Querida. Photo by Konee Rock.

CV: This wasn’t your only trip with the program, though. What came after that?

D-I: In 2024, Next Level assembled an All-Star crew of ambassador alums from previous years to travel to Paris to perform and connect with artists there, too. The hip-hop community there is very strong, and I got to be part of an open mic cypher that featured around 40 MCs, repping many different nationalities and languages, at Canal 93 venue in Bobigny. We felt especially honored to perform at Place de la Concorde, just before the Olympics, surrounded by all the amazing art and architecture. After that, our final event in Paris was an all-elements showcase at the U.S. Ambassador’s house—the first hip-hop jam ever held there, according to the security guards.

CV: How did your more recent travel to and collabs in Colombia come about?

D-I: I’d been asked by this organization called Coopdanza to write story-raps (in English) for a theatrical piece written by an Indigenous artist in Colombia, Eina La Majayut, about a Wayúu woman confronting the invasion of her People’s land by a mining company that arrived to extract its coal. The story resonated for me as I could see intersections between what Indigenous Peoples in Colombia were facing and what’s been happening to us here in the U.S.

At Standing Rock, for example, the NoDAPL movement related what was happening with the pipeline to a Lakota prophecy about a destructive black snake that would come to threaten their land and water. The Wayúu People, as it turns out, have their own story about their own black snake, called Cerrejón, which they, in turn, relate to the destruction caused by mining in their territories.

I was later invited to Bogotá to perform these songs on stage during SIE 2: Festival Indígena de Danza y Artes Mediales.

CV: Were you able to meet with other hip-hop artists there as well?

D-I: Yes. One that’s important for me to mention is Gailor Sanchez (also known as The Jaguarman), a dancer and rapper who represents his culture and heritage by infusing hip-hop with traditional drum beats, flute sounds, and other instruments. Jhon Jota, from the Naza People, is another great Indigenous artist I met, and we got to shoot some videos together on my last day in Bogotá.

In Abuja, Nigeria with artists Iyalode, Dorino, Nomiis Gee, Ami Kim, Osharey Ghaga, T-Klex, B-Boy JC Jedor, from the local hip-hop community. Photo by Petna Ndaliko Katondolo.

CV: You’ve gotten to open for and tour with a variety of internationally notable U.S. artists here over the years. Let’s hear a roll call of the most memorable.

D-I: Sure. I’ve been on the Vans Warped Tour, I’ve opened up for Nelly, for GZA (of Wu-Tang Clan), Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Wiz Khalifa, Immortal Technique, Tech 9, Onyx, Dead Prez, DMX, Hieroglyphics, Big Daddy Kane, Sir Mix-a-Lot, and Freestyle Fellowship. I’ve toured with Masta Ace from the legendary Juice Crew quite a bit and with others like Kool Keith, Abstract Rude… there are a lot.

CV: Meanwhile, you have continued to be a very active part of the parallel Native hip-hop scene happening across Turtle Island, visiting and doing shows for many Reservations. What have you found to be distinct about those experiences and audiences?

D-I: Performing in front of Rez crowds really made me think more about who I am and what I represent in hip-hop. Besides my own Reservation, I’ve performed everywhere from Pine Ridge (South Dakota) to Red Lake Nation (Minnesota), Lenapehoking (New York), on Tongva Lands and the Poma Nation in the Bay Area (California), in Alaska, and close to home for the annual Gathering Of MCs in Albuquerque.

Some of these crowds that come to the Rez tours may never have been to a “live” hip-hop show before, as they don't usually have access to them. It feels special to me then, being able to bring my music there; different from performing for a city crowd.

Before and after every Rez show, I make time to connect with the people of each community. We’ll do trades and share medicine bundles and stories. I get music passed on to me sometimes as well, and I’m always quick to lend an ear—especially to artists that choose to rap in a language other than English.

CV: Finally, please tell us about your recent music release with Acid Reign and producer Duke Westlake, the song “Reign Dance”—and share a bit of your verses from it to inspire.

D-I: We actually recorded that track a few years ago, but now the album is finally out. Getting to work with Acid Reign—Olmeca, BeOnd, and Gajah (now R.I.P.)—was a huge honor; together we were also part of Project Blowed. Those guys came out of the legendary scene at The Good Life in 1990s L.A.

I’ll leave you with this from “Reign Dance”:

“I wish they would spit with a little bit of validity/ Focus your energy to the best of your humility/ That’s how we reign dance, bring the weather and humidity/ Indigenous infinity unlimited delivery/ Move with music, shine bright with the band/ With the mic and the stand/ When I’m right by my fam/ As we light up the plant and ignite with the chant/ Reign dance for the villages, the people and land.”

--Cristina Verán is an international Indigenous Peoples-focused researcher, educator, advocacy strategist, network weaver, editor, and mediamaker. She was a founding member of the United Nations Indigenous Media Network and the Indigenous Language Caucus. As Adjunct Faculty at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, she brings emphasis to the global histories, expressions, and socio-political impacts of Indigenous contemporary visual and performing arts, design, and popular culture(s).

Top photo: In Bogotá, Colombia with hip-hop artist Jhon Jota. Photo by Def-I.