More than a resistance, the Indigenous movement is inspired by strong community and family ties. It is strengthened collectively with new languages, knowledge, and forms of political action. Newiwe Top’Tiro (Xavante/A’uwẽ Uptabi), Aptsi’ré Waro Juruna (Juruna/ Xavante), and Roiti Metuktire (Kayapó/Mebengôkre/Juruna) are three of the countless young activists and leaders of the Indigenous movement. In a recent conversation with Cultural Survival, we asked them about the heritage and legacy of the ancestral struggle that brought us here, about the transmission of values, memories, and strategies of struggle between generations, and about dreams, a central institution for many of our Peoples, in building an ancestral future.

Newiwe Top’tiro (Xavante)

Newiwe Top’Tiro is the daughter of Hiparidi Top’Tiro, the renowned A’uwẽ-Xavante leader celebrated for his tireless defense of the Cerrado biome and his powerful international advocacy. She is now an archaeology student driven by her desire to research and reclaim the ancestral sites of her Peoples in the heart of Brazil.

It took me a while to understand how the movement worked and what my father really did. He always told stories about my grandfather [Sibupa], about his journey through the city, and especially about the power our family name carried. He and my mother always did their best to ensure my sister and I had a good education and went on to higher education, and that was our focus until we were about 15.

From that age onward, we began to interact more with the Indigenous movement and see the scale of this universe and what my father was involved in. I knew what was going on from the top down, and I saw my father at meetings and on trips, but not the depth and scope of what he accomplished. I always saw him as a strong man and admired him. He always told many stories interspersed with jokes. I now view him with great respect, as an incredible man and warrior, as a friend and advisor on our journey.

The struggle of the previous generation was undoubtedly great. They faced countless challenges so that today we can be recognized and heard. I know my father suffered greatly when he left the village to enter university at a time when few Indigenous people occupied these spaces. There was a greater openness [then] to entering politics and the media, drawing attention to the importance of protecting our lands and culture. They faced tough battles and much suffering so that my generation could occupy the spaces we have today and have an active voice within the movement.

I believe that the Indigenous movement is still constantly evolving and always will be. As time passes, changes occur, and this is reflected in us as well. Although there are fundamental principles for which we continue to fight, it is clear that many transformations have already occurred.

One of these important advances is the strengthening of women’s active role in the movement. Increasingly, strong women are gaining prominence and occupying leadership positions. I proudly mention my aunts, Bernardina, Berenice, and Tstsina, admirable women whose work deserves full recognition. Perhaps I don’t feel “responsible” to do the same; no one does anything alone in the Indigenous movement. For me, it’s not just about resistance, but also a gesture of gratitude for everything my People and my village have done for me. I will do whatever I can to contribute and raise awareness, both on behalf of my People and in support of the Indigenous movement as a whole.

Regarding my father’s influence, I constantly think about how I can seize the opportunities that arise to continue on this path. The course I’m taking today and the projects I’ve participated in are examples of this. I’m very proud of my roots and want to expand the reach of the Indigenous movement and invite others to learn about and connect with this struggle. And I’m not just talking about non-Indigenous people, but also about relatives who haven’t yet actively participated.

I’m noticing that more and more young people are becoming interested in actively participating in the Indigenous movement, bringing to the forefront debates that previously weren’t as widely discussed. One of the most important resources we have at our disposal today is social media, and it’s wonderful to see how we’re occupying these spaces strategically and creatively.

I’m happy to see that through these platforms, we’re able to show who we truly are and deconstruct the stereotypes imposed by non-Indigenous perspectives. We’re using digital tools not only to communicate, but also to affirm and empower ourselves and connect with other realities. I’m also struck by the growing number of young Indigenous communicators—people who use their cameras, cell phones, and creativity to record, narrate, and share their experiences, cultures, and struggles. This has had a significant impact both within and outside our communities.

I know there’s an expectation that we be active within the movement, but in my case, I’ve never been forced into anything. My father never forced me; he simply showed me, through example and words, how we can contribute to improving our village, strengthening our bonds, and communicating with other Peoples. He always encouraged us to use whatever we choose to do, whether it’s study, a career, or a project, as a way to move forward, always keeping our family in our hearts, regardless of distance, just as my mother also taught [us]. This support inspires me greatly.

I see that the Indigenous movement is on a good path, and I know [my parents] are proud of it—not only of what we do, but of the way we manage to honor what we were taught, looking to the future without forgetting where we came from.

Aptsi’ré Waro Juruna (JURUNA/XAVANTE)

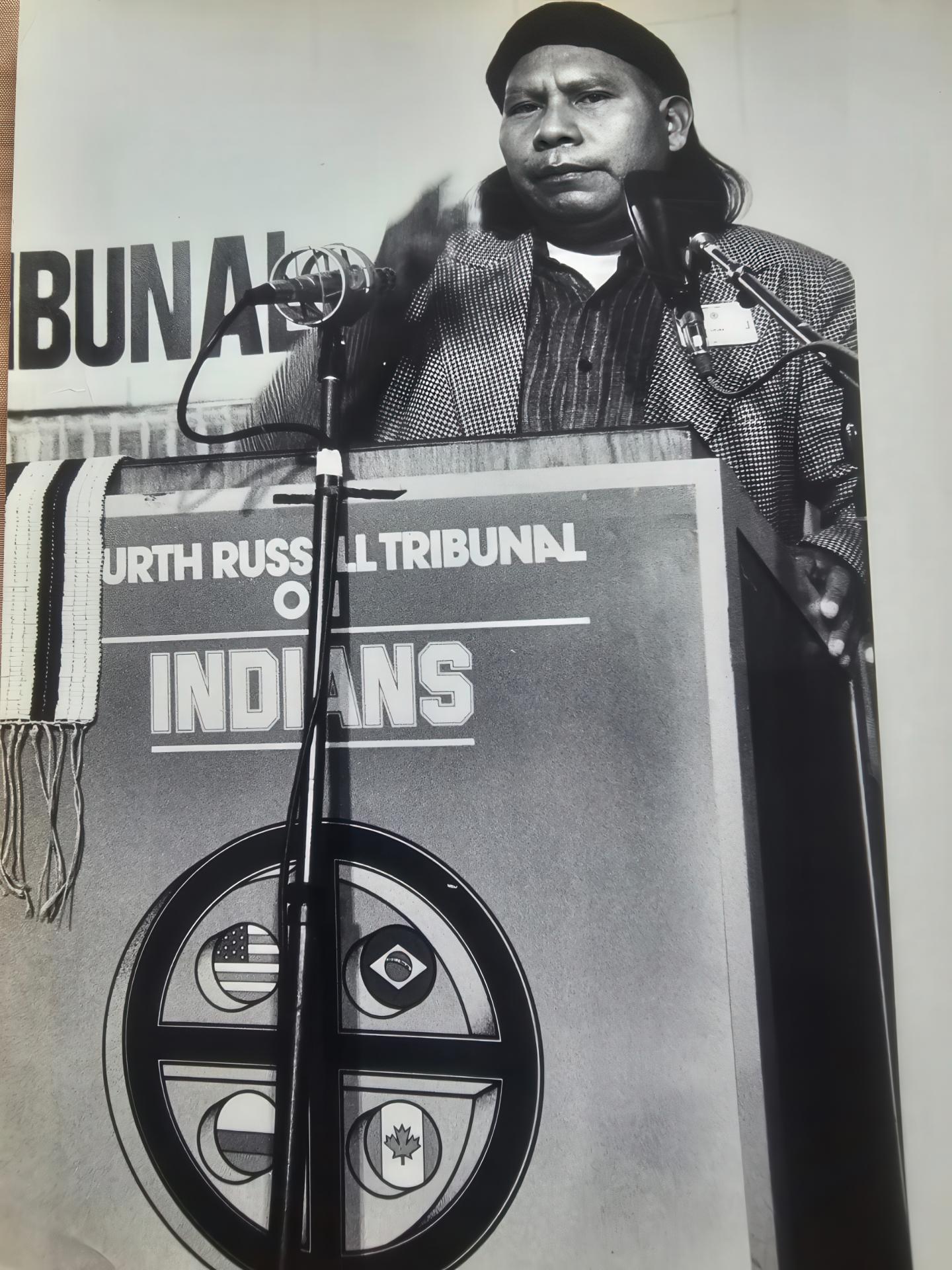

Aptsi’ré Waro Juruna is the son of the late Xavante chief Mário Juruna, the first Indigenous person to hold a parliamentary seat in Brazilian history. He is currently a student at the University of Brasília, where he is pursuing a double degree in Social Sciences and Anthropology. He also works as a collaborator and political supporter for the Xavante Warã Association, and holds a Fellowship with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Since my early childhood, I have observed the passage of many Indigenous leaders from many Peoples of Brazil, non-Indigenous leaders from the national political scene, and also Indigenous leaders from other countries who frequented our home. Many came to meet my father, and others to continue various activities aimed at Indigenous Peoples. During this same period, they recounted, as was customary, the origin of the traditional, strong political lineage of our Aptsi’ré family—Aptsi’ré was my father’s grandfather—which permeates among the A’uwe Xavante to this day. This process has remained in my memory, as I was able to have contact with people from diverse cultures around the world who frequented our home.

As a child, I didn’t fully grasp what was happening, but in my perception it was something very natural and even commonplace. However, as the years passed, I gained a true understanding of my family nucleus. I also learned through newspaper clippings, television news, and history books that recounted my father’s great historical feats in favor of the Indigenous struggle. This was very moving for me, and continues to be so.

We cannot disregard the sense of cultural authenticity of older generations and their understanding of the external attacks that surrounded them, or their alliances of struggle and mobilization with other Indigenous Peoples from Brazil and other countries that also experienced similar situations of injustice and violence. This relationship needs to be monitored as closely as possible, and this requires that we, the current generation of Indigenous Peoples, continue to provide access to tools and mechanisms for protection of our rights to other relatives who still have limited or no access to this type of information. Therefore, I believe our role is to bring workshops and training in various areas to the villages in social areas such as education, health, politics, land rights, and culture, so that they can have a better understanding and dimension of such situations.

In my view, anyone who has real access to this information is obligated to pass it on to other groups that do not have this access. Such information must be conveyed in a reliable manner and [made available] in the languages of these Peoples who are being attacked by policies that aim for cultural assimilation of our cultures and territories. This legacy carries a great deal of responsibility and, at the same time, a certain naturalness when you realize that through your actions, you can help many other people you might never meet. [As the saying goes in Brazil], “If you have greater access to water, you are obliged to quench the thirst of others who don’t have access to water.”

The occupation of Indigenous people in political decision-making spaces in the government and in their grassroots organizations in Brazil and internationally is a reflection of this positive change. Our definitive insertion into these spaces where we previously did not exist, and being represented in these spaces, is a fundamental and necessary strategy for the continuation of our struggle.

Despite having cultures different from other Indigenous Peoples, the link that connects us with other Peoples and cultures is our confrontations with policies that aim to diminish our human rights as Indigenous Peoples. The struggle we face will continue with our children, our grandchildren, and with the future generations yet to come who are being prepared to occupy these positions. The Indigenous struggle will not end as long as there are Indigenous people who still do not know how to fight for their rights.

We must remain strong with our cultures and customs in a single movement, aiming for the collective good and the preservation of our ways of life, and, consequently, that of our ancestral territories. Because that is where our strength comes from: it comes from nature, and we belong to it and protect it.

Roiti Metuktire (KAYAPÓ/MEBENGÔKRE/JURUNA)

Roiti Metuktire lives in the Capoto/Jarina Indigenous Territory in Mato Grosso. He is the son of Bedjai Txucarramãe, an important leader of the Kayapó people, and Darayo Ware Juruna (Juruna), from the Xingu territory.

Since my youth, I have been guided by Traditional Knowledge and the example of my parents’ struggle, especially regarding the defense of the land, culture, and life of Indigenous Peoples. My journey is marked by deep respect for ancestral roots and an ongoing commitment to environmental protection.

Since 2006, I have been involved in the activities of the Raoni Institute, from volunteer to Territorial Management and Protection Coordinator. In this position, I have played a fundamental role in strengthening monitoring and surveillance actions in the defense of Indigenous territories, supporting communities in protection strategies against invasions and deforestation, and other external and internal threats such as climate change.

In addition to my technical work, I am recognized as an Indigenous activist committed to environmental causes and the protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples. I participate in forums, meetings, and political articulations at the local and national levels, bringing the voice of the Kayapó and other forest Peoples to decision-making spaces.

My dedication reflects the continuity of a historic struggle and the hope for a future where Indigenous territories are respected and preserved as living heritage sites of humanity. I am inspired by the struggle of my great uncle, Chief Raoni, a leader who always used these wise words: “We breathe the same air, we drink the same water, so it is our duty to take care of what we have so we can have a forest for our children and grandchildren.” With this thought, he expressed to the world his concerns about human-caused changes to the earth and what could happen if we don’t take care of it.

I am inspired by the respect my great uncle earned throughout his life of struggle. He fought so hard for Indigenous Peoples to be respected. Even though it was often difficult and many people didn’t understand his concerns, he never gave up and always maintained his strong spirit. He urged Indigenous Peoples to be more united, and it’s my duty to carry on his legacy.