Rematriation is more than the return of land or cultural items. It is a sacred process of restoring Indigenous relationships to land, water, language, and spiritual responsibility. Where colonization sought to sever these relationships, rematriation centers Indigenous women, matrilineal knowledge systems, and cultural continuity to heal what was disrupted, displaced, or violently stolen. The term itself challenges the dominant colonial concept of “repatriation,” which often frames the return of objects or remains to Tribal communities as a bureaucratic or institutional gesture. In contrast, rematriation is a spiritual and political act of reconnection, one that reclaims Indigenous worldviews where land is not property but kin, where leadership emerges from responsibility, not hierarchy, and where women are the carriers of life, law, and legacy. As an Indigenous rights advocate, educator, and founder of 7 Directions of Service, rematriation is at the heart of everything I do. I have spent years protecting sacred sites from environmental destruction and standing against pipelines that threaten burial grounds, waterways, and ancestral territories. These efforts are not only acts of resistance, but also remembrance and return. They are rematriation in motion, guided by the voices of our grandmothers and the needs of future generations.

Rematriation is not always peaceful. It often begins in the face of erasure and extractive violence, pipelines, highways, gravel pits, and development projects that proceed without consent and ignore the sacred. Indigenous Nations like the Occaneechi, Tuscarora, Meherrin, and Lumbee continue confronting these threats in the southeastern United States. Many of us, unrecognized federally or overlooked by state systems, must fight twice as hard to defend our lands and ancestors. When I stood before the threatened sites along the Mountain Valley Pipeline Southgate Extension and the Southeast Supply Enhancement Project, I wasn’t just opposing fossil fuel infrastructure: I was protecting our Peoples’ right to exist on the land. These burial sites, forests, and rivers are not relics. They are living archives of our history, prayer, and sovereignty. In the colonial imagination, land was a resource to be controlled. But to us, land is a ceremony, a grandmother, and a memory. That is why our resistance is about stopping destruction and restoring our responsibility to the land as a relative. This is the core of rematriation.

Jason Keck and Crystal Cavalier-Keck proudly with their new tractor, a vital tool for expanding food sovereignty and stewardship at Yesah Farm.

A Personal Journey of Return

Rematriation has deeply personal meaning within my own Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation. Our people have endured centuries of displacement, broken treaties, and misrecognition. Despite that, we’ve held onto what we could, fragments of stories, foods, ceremonies, and burial grounds that tie us to our ancestors. I have worked to help document and protect ancestral sites along the old Occaneechi Trading Path—an ancient route that once connected tribes from the Great Lakes to the Carolinas. This land is not a metaphor; it contains the bones of our people, the tracks of our trade, and the teachings of those who walked before us. Rematriation here means restoring ceremony and self-governance. I have supported the revitalization of traditional foodways and public education around our sacred places. I continue to advocate for constitutional reform in our Tribal governance so that our leadership structures reflect Indigenous values of balance, consensus, and circle, not colonial mimicry. I work to ensure that women, Elders, and youth, those traditionally silenced, are once again central to decision-making.

Through our organization, 7 Directions of Service, we’ve developed programs that bring these ideas to life. Our youth river journeys are not just summer outings; they are immersive experiences rooted in land-based pedagogy, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and intergenerational learning. Youth learn how to identify medicinal plants, trace the rivers of their ancestors, and engage in community-based environmental stewardship. We teach them not just how to survive, but also how to listen to the water, the trees, and their Elders. We help them understand that the land remembers them, even when systems try to erase them. In doing so, we prepare the next generation of land protectors, culture-bearers, and tribal leaders. This kind of education is not optional—it is essential. In a time of climate crisis, cultural erasure, and rising youth mental health disparities, reconnecting our young people to land and identity is both a form of healing and a blue- print for survival. Rematriation offers more than a return to tradition; it provides a path forward.

Jason Keck and a dedicated volunteer planting blueberry bushes during Fall community planting day.

Land Back and Ceremony Forward

Rematriation is often linked to the “Land Back” movement, but it goes deeper than land return alone. Land Back is a critical demand for justice, but rematriation adds the spiritual, ceremonial, and gendered dimensions that reflect how we relate to land. It asks: Who will steward this land? Who will sing for it, pray with it, raise children on it? In many nations, that responsibility belongs first to women—life-givers, knowledge keepers, water protectors. Colonization displaced not only our people, but also the roles we held within our societies. Rematriation re-centers Indigenous women’s leadership in theory, ceremony, governance, and land stewardship. You cannot restore the land without restoring the systems that once protected it, and grandmothers guided those systems.

Too often, rematriation is mistaken for the return of artifacts in museum vaults. While returning ceremonial items, wampum belts, and ancestral remains is vital, we must understand that these items are sacred because they are part of something larger. They are expressions of cosmology, kinship, and responsibility. True rematriation returns not only the physical, but also the spiritual and cultural wholeness that those items represent. It restores language, songs, food, governance, and memory. It returns to us what was taken and invites us to pick up what was left behind. I’ve witnessed this firsthand when young people taste traditional foods grown in repatriated gardens, participate in coming-of-age ceremonies that were once banned, or see their river as a water source and an ancestor. These moments transform them—and us.

The Role of Women in Indigenous Futures

Indigenous women have always been at the forefront of protection movements, resisting boarding schools, organizing against pipelines, reviving ceremonies, and demanding accountability from our institutions. We are not just survivors of colonial violence, but builders of post-colonial futures. Rematriation honors this leadership. It moves beyond inclusion and toward restoration. It asks not, how can we make space for Indigenous women? But how can we return to a world where their leadership is the foundation? This means addressing not only external systems of oppression, but also the internalized structures that have sidelined our voices in tribal politics, organizational hierarchies, and movement spaces. If rematriation is to succeed, it must be practiced in governance, in institutions, and everyday relations.

Rematriation is not a metaphor. It is a daily practice of living in proper relation with the land, each other, our ancestors, and those yet to come. It requires humility, accountability, and ceremony. It means listening more than speaking, tending more than taking, and leading from the heart rather than the podium. For me, it is not an abstract idea; it is the way I live, teach, and lead. It shows how we farm, organize, resolve conflict, and prepare our youth. As we continue this work in North Carolina and across Turtle Island, I invite others to join us in protest and practice. Rematriation is a return, but also a reawakening. It is an invitation to all Indigenous Peoples to remember who we are and to live accordingly. When we repatriate land, we don’t just restore territory; we restore law, love, and life. And that is how we begin to heal.

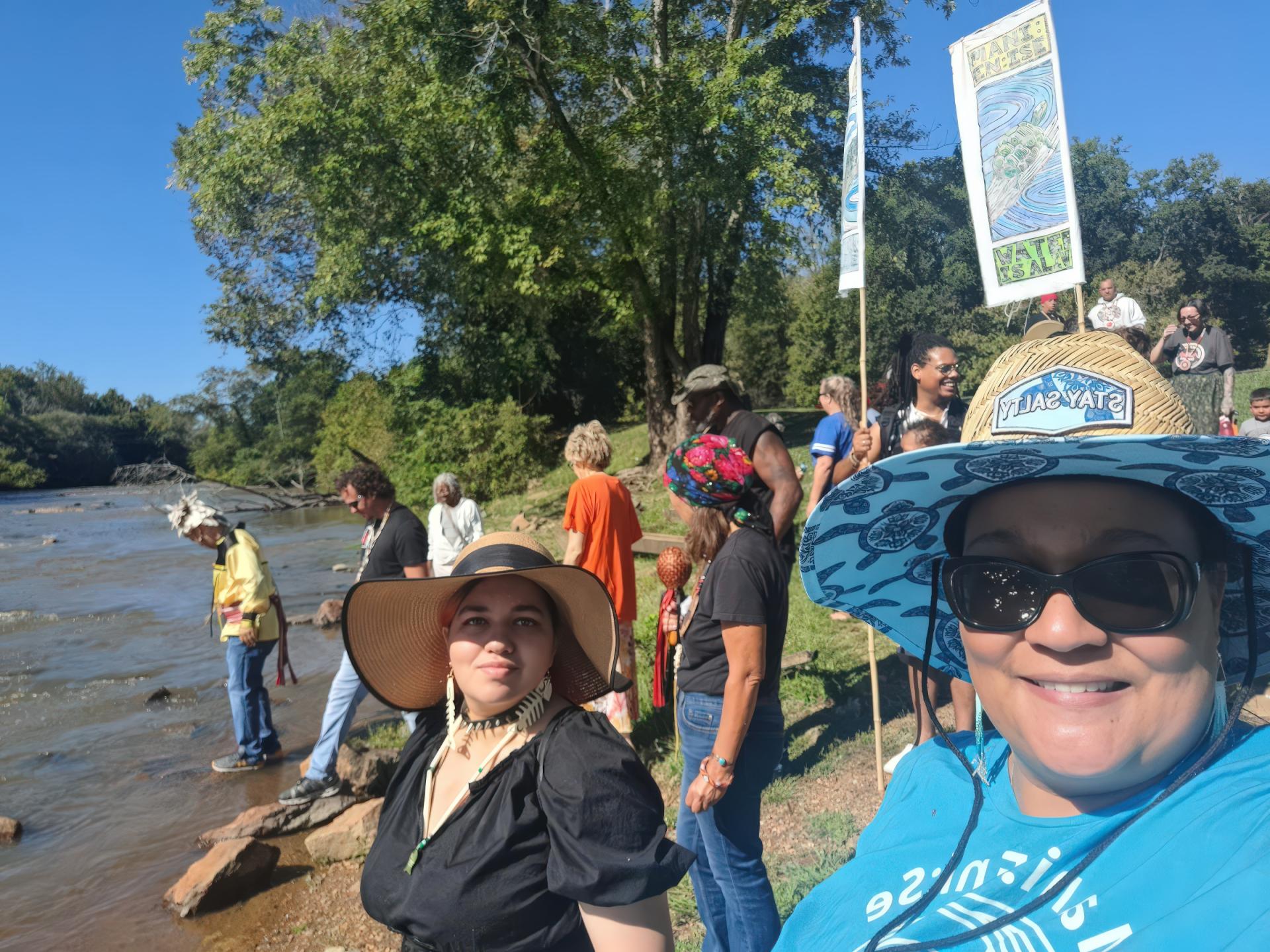

A community workday with dedicated 7 Directions of Service volunteers.

Dr. Crystal Cavalier-Keck (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation) is the founder and Executive Director of 7 Directions of Service, an Indigenous-led collective rooted in environmental justice and community organizing based in the homelands of the Occaneechi-Saponi in rural North Carolina.

Top photo: A view of the backyard at Yesah Farm in Mebane, North Carolina, where community, culture, and cultivation come together.

All photos courtesy of 7 Directions of Service.